Navigating Troubled Waters

Xi Jinping, Monopolized Power, Overproduction, and the Mandate of Heaven

Xi Jinping has amassed more power than any Chinese leader since Chairman Mao Zedong, but even the Great Helmsman knew that you have to pay close attention when you navigate the ocean. As his Great Leap Forward led to mass starvation, he launched the Cultural Revolution to deflect and topple his critics. Xi has proved himself a shrewd and pragmatic leader, but will this be enough to hold on to power, and overcome China’s deep-rooted economic problems?

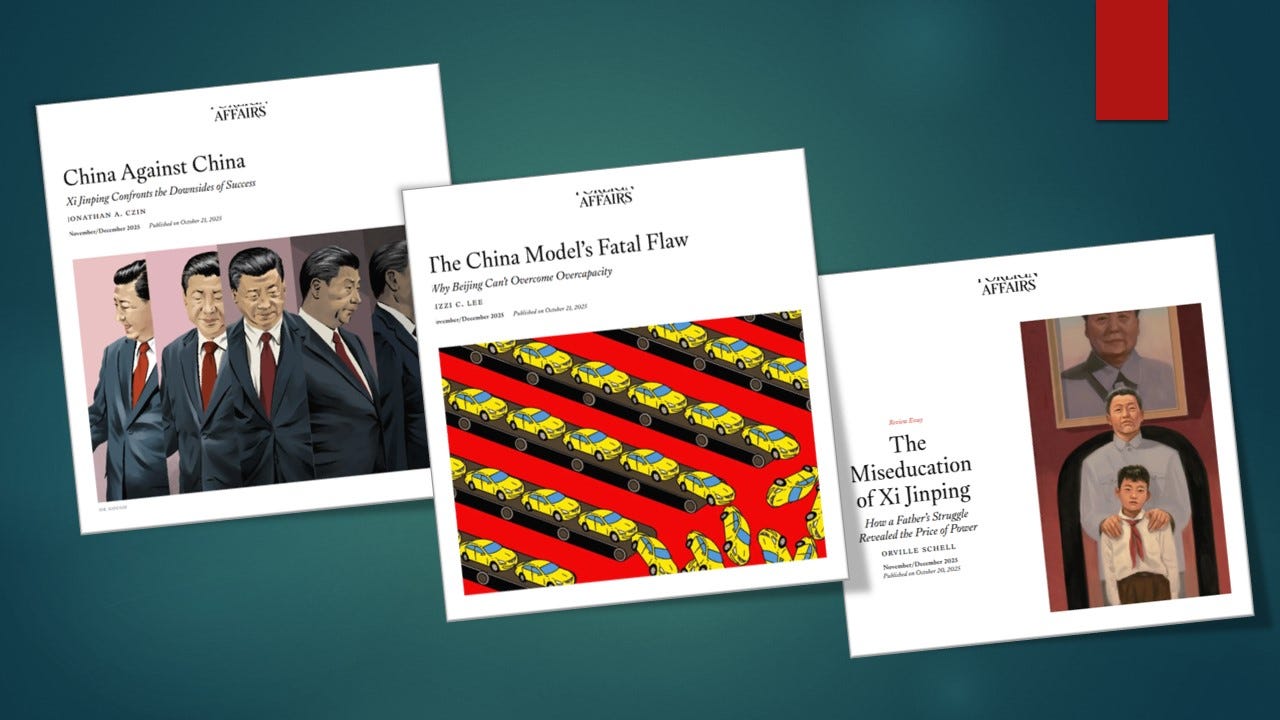

Xi Jinping grew up in a very, very different environment from Mao’s, something made clear in Joseph Torigian’s biography of the elder Xi, The Party’s Interests Come First: The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping. The veteran China observer Orville Schell reviewed Torigian’s book for Foreign Affairs.

Neither devotion nor loyalty could save Xi Jinping’s father from the nightmarish but very real terror Mao inflicted on enemies and loyalists alike. The young Xi saw all this close up as a child and was even betrayed by his mother who turned him over to the authorities when he had snuck home from school one night to ask her for food.

(Two good historical novels about China are Ha Jin’s The Woman Back from Moscow, Other Press, 2023, and Orville Schell’s My Old Home: A Novel of Exile, Pantheon, 2021. )

The young Xi saw all this close up as a child and was even betrayed by his mother who turned him over to the authorities when he had snuck home from school one night to ask her for food.

The Xi family’s nightmare didn’t end until after Mao’s death in September 1976 and Deng Xiaoping’s subsequent return to power. The elder Xi was then allowed back to Beijing and played a key role in the economic reforms until his death in 2002. What impact did all this have on young Xi?

“Many mistakenly thought Xi would follow in his father’s reformist footsteps and that China might slowly evolve into a more collective form of leadership, adopt a rule-of-law-based system, and welcome a more liberal economy. Torigian’s book offers a wealth of clues as to why these hallmarks have not ended up distinguishing Xi Jinping’s tenure.” (Orville Schell, The Miseducation of Xi Jinping, Foreign Affairs, Nov/Dec 2025.)

Dealing with authoritarian systems often puts an emphasis on the supreme leader. Jonathan A. Czin, who followed China at the CIA, the NSC, and is now a fellow at the Brookings Institution, lays out the difficulties analyst face when trying to understand Xi’s rule in his essay China Against China (Foreign Affairs, Nov/Dec 2025.)

“To some, Xi is the second coming of Mao, having accumulated near-total power and bent the state to his will; to others, Xi’s power is so tenuous that he is perpetually at risk of disgruntled elites ousting him in a coup.”

Xi managed to outmaneuver his rivals and concentrate power in his own hands, but this means that he carries the responsibility if anything goes seriously wrong. This is something Deng must have understood, and one result of his decentralizing economic reforms (besides rapid economic growth and happier peasants who could sell their produce at free markets) was to create some space between the Communist Party and the people. Meddling less in people’s private affairs would to some degree insulate the party from criticism (Big exceptions were the One-Child-Policy under Deng, and the COVID-19-policy under Xi).

Deng’s reforms created a profit-oriented market economy within the general framework of a state-controlled economy, but they also undermined the communist ideology.

“For Xi, China’s most glaring weaknesses are the side effects of four decades of economic reform. Rapid growth brought wealth and power but also indecision, corruption, and dependence on other countries,” Czin writes.

One thing that could have countered the widespread corruption and abuse of power would have been the “Fifth Modernization” that Wei Jingsheng and other dissidents called for (but which landed them in prison or exile). Without a free press/independent mass media, an independent judiciary, and other key components of a democratic system, decentralization is likely to breed corruption.

Xi picked another path, that of the late veteran leader Chen Yun, which he celebrated this past June. Orville Schell suggests that one explanation for Xi’s choice could have to do with his and his family’s suffering under Mao.

“…the best protection against being viewed as an apostate was to become more orthodox than anyone else.”

This is understandable, considering China’s two millennia of authoritarian rule. Xi had learned a hard lesson, and ended up adopting much of Mao’s style, leaving his portrait overlooking the Tiananmen Square.

Xi had learned a hard lesson, and ended up adopting much of Mao’s style, leaving his portrait overlooking the Tiananmen Square.

“Concentrating power in Xi’s hands was the obvious corrective. Xi has used his centralized power to move away from policies that would further liberalize China’s economy and toward efforts to enhance China’s economic and political resilience,” Czin writes.

Lizzi C. Lee takes a different perspective in her essay The China Model’s Fatal Flaw (Foreign Affairs, Nov/Dec 2025.) She is an expert at the Asia Society’s Center for China Analysis. Instead of reading the politburo’s tea leaves, she looks at the underlying economic machinery, the structures and incentives behind China’s explosive economic growth especially when it comes to electric cars, batteries, and solar panels. This triggered accusations from China’s major trading partners that they engaged in “unfair government subsidies,” but the Chinese government had already cut the solar power subsidies four years ago and phased out their subsidies for electric vehicles and batteries. Which didn’t stop them from expanding, cutting prices, and focus even more on export. Lee sees “a more sinister and systemic” explanation for this development.

“The real challenge, then, lies not in weak domestic demand or excessive state handouts but in an extraordinary and seemingly uncontrollable surge in supply—one that Beijing is struggling to get its arms around. Since mid-2024, central government authorities have warned repeatedly about ‘blind expansion’ in solar power, batteries, and EVs. This summer, after a brutal price war in the solar industry saw prices fall around 40 percent year-over-year, Chinese leaders directed officials to tackle overcapacity and ‘irrational’ pricing in key industries, including solar. Shortly thereafter, high-level officials met with industry leaders to collectively urge companies to curb price wars and strengthen industry regulations.”

When leaders of a socialist state complain about “blind expansion” and “uncontrollable surge in supply,” one cannot help but hear echoes of Karl Marx’s prediction that the capitalist system leads to overproduction as competition causes companies to invest in ever larger capacity while replacing labor with machinery and undermining consumption.

…one cannot help but hear echoes of Karl Marx’s prediction that the capitalist system leads to overproduction as competition causes companies to invest in ever larger capacity while replacing labor with machinery and undermining consumption.

We tend to assume that enterprises in a socialist country are owned and controlled by the state, which used to be the case in China since it initially copied the Stalin model, where state ownership dominated in industry and collective farms/people’s communes dominated in agriculture. However, Deng’s economic reforms, which began in 1978, changed the business landscape, thereby limiting the party’s direct control of the economy.

As a result, most businesses in China are not owned by the government. There are 56 million private enterprises and 125 million individually owned household businesses. Together they contribute about 60 percent of GDP and provide 80 percent of urban employment (Jamie P. Horsley, Brookings, May 28, 2025.) The late British economist Peter Wiles once wrote that China’s state-owned sector is “an island in the capitalist archipelago.”

The ultimate power still lies with the Communist Party leadership, which can use both direct and indirect means to steer the economy and punish companies and their leaders if they don’t follow the official policy. However, the party leadership must consider how their policy impacts the regime’s legitimacy (traditionally the Mandate of Heaven) if it leads to unemployment, inflation, and stagnation.

Lee points to “structural incentives” behind the overcapacity.

“China’s tendency to overproduce starts in an unlikely place: the Chinese Communist Party’s performance and promotion system. In the CCP bureaucracy, local officials are evaluated primarily on their ability to deliver growth, employment, and tax revenues. But China’s largest single tax, the value-added tax (VAT), is split evenly between the central government and the local government of the place where a good or service is produced, not the place where it is consumed. Since the system allocates tax revenue to regions based on production, it rewards the decision to build larger industrial bases. Local Chinese officials try to retain as much upstream and downstream activity as they can to expand their tax base. (The U.S. tax code, by contrast, apportions much of the corporate tax base to where companies’ customers are, rather than where firms produce goods, so the tax base is more evenly spread across jurisdictions.) This feature of the Chinese tax system explains the proliferation in China of ‘full stack’ industrial clusters: EV assembly lines are located near battery production facilities, and solar panel factories are integrated with raw material and component suppliers.”

China’s banking system, which is dominated by state banks, plays a key role in guiding and controlling the economy, but it has a conservative rather than entrepreneurial slant. Lee writes:

“Persistently low profit margins also mean companies have little cash to reinvest in product development and hiring; that in turn depresses household income growth and consumer demand. In this way, overcapacity becomes more than just a sectorial problem: it acts as a drag on China’s broader economy, locking it into a cycle of low profits, weak investment, sluggish job creation, and consistently weak demand.”

Large private companies may seek alternative financing domestically or in global equity markets, but that leaves them vulnerable to sudden policy shifts either in China or internationally. The party tries to steer the economy in one direction, but the incentive structure and tax system encourages entrepreneurs, managers and local officials to take the easy way out: “copy quickly, scale up even faster, and price aggressively.” Hence the overcapacity.

This requires a radical change of the economic system, but this is hard for a party leadership that is risk aversive.

“In this sense, unwinding overcapacity is not just an economic adjustment. It is the ultimate test of Beijing’s ability to self-correct—and of whether the Chinese model has reached a plateau or can once again soar to new heights,” Lee writes.

Whether Xi will remain the Helmsman will depend on whether he can keep China’s people happy (by providing jobs, incomes, and living quarters) without exasperating the trade conflicts with China’s biggest customers. His priority so far has been to preserve the system of power, but that may not be enough.