A Coffee Break Is Better Than Confucius

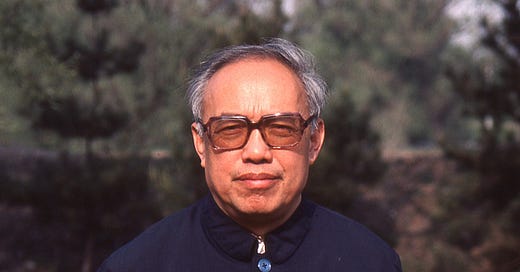

My 1985 Interview With Professor Guo Kexin, Member of Academia Sinica

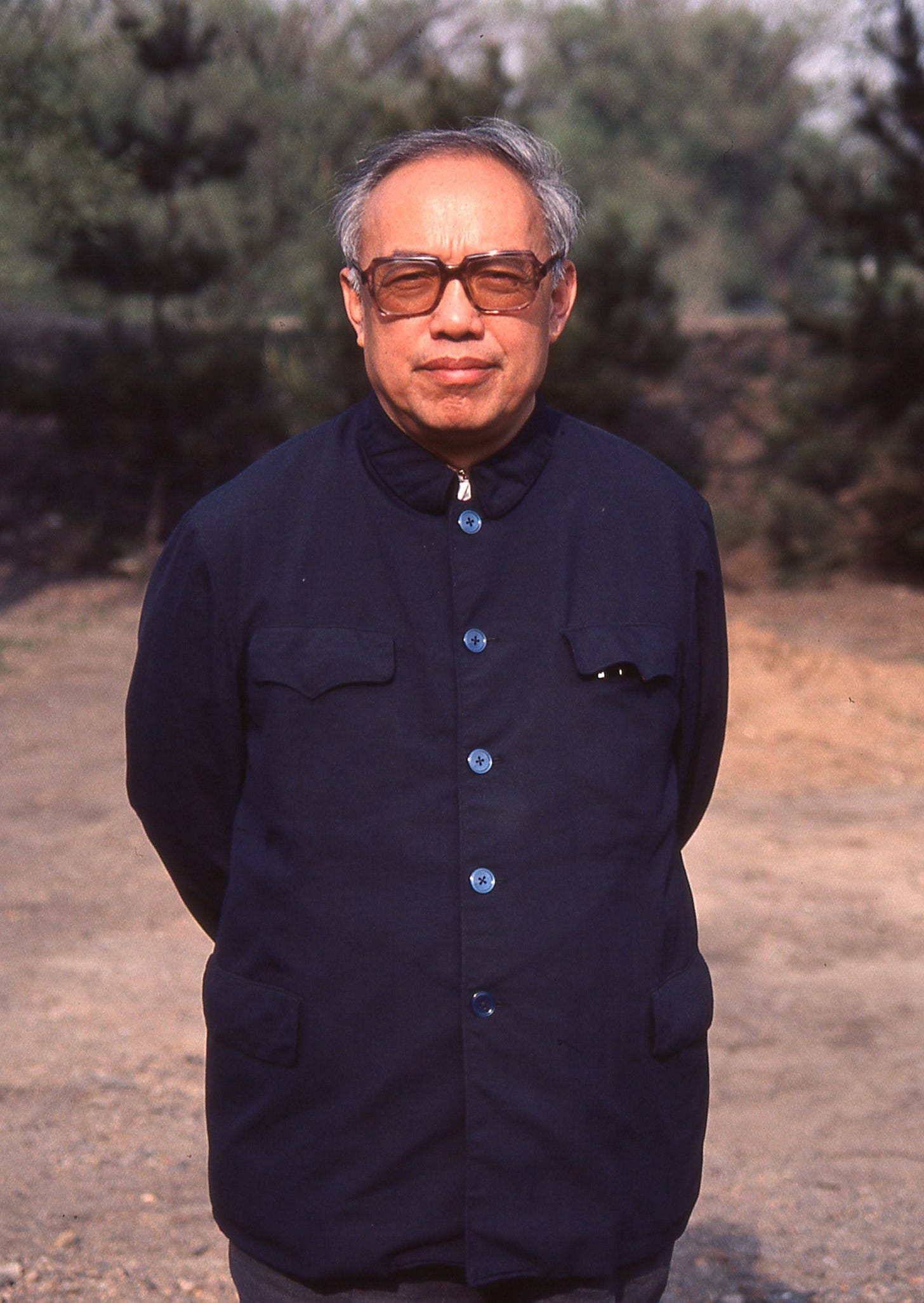

The other day I read an interview with Ren Zhengfei, the founder of the telecom and electronics giant Huawei. What this great entrepreneur said about creating good conditions for science and research brought me back to 1985, when I interviewed Professor Guo Kexin (1923-2006), a member of the Chinese Academy of Science in Shenyang, a city in northeastern China. The interview with Ren Zhengfei ran on the front page of People’s Daily (June 10, 2025), the official newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party.

An English translation is available on Manoj Kewalramani’s substack Tracking People’s Daily and on Jordan Schneider’s ChinaTalk substack.

The title echoes the mood of the mid-1980s.

Ren Zhengfei stresses both the need to allow basic research to work freely and to take a long perspective.

“When our country possesses certain economic strength, we should emphasize theory, especially basic research. Basic research doesn't just take 5-10 years—it generally takes 10, 20 years or longer. Without basic research, you plant no roots. And without roots, even trees with lush leaves fall at the first wind. Buying foreign products is expensive because their prices include their investment in basic research. So whether China engages in basic research or not, we still have to pay—the question is whether we choose to pay our own people to do this basic research.”

Jordan Schneider, founder of ChinaTalk, writes in his introduction to the article:

“The People’s Daily giving Ren Zhengfei the airtime to promote this view underscores just how central China’s leadership today sees this work.”

One thing that struck me was Ren Zhengfei’s was his comment on the “Huang Danian Tea‑Thinking Room” at Huawei’s headquarters outside Shenzhen in the Guangdong province. Here students were offered free coffee so that they could “absorb cosmic energy over a cup of coffee.” At the end of the interview he says that “the country is becoming increasingly open, and openness will drive us to greater progress.” In the next sentence he does of course pay his dues to Chinese political correctness by extolling the “Party leadership,” but this is probably a matter of self-protection from a man who survived the Cultural Revolution.

Back to Professor Guo Kexin whom I met in Shenyang during my first journey through China. I doubt that he would have given me — a Swedish backpacker and freelance journalist — an interview if it wasn’t for the fact that he had lived in Sweden and spoke Swedish.

The interview was published in Gaudeamus (March 10, 1986), a student newspaper at Stockholm University. Below is my English translation:

From KTH to China’s Academy of Sciences

A Coffee Break Is Better Than Confucius

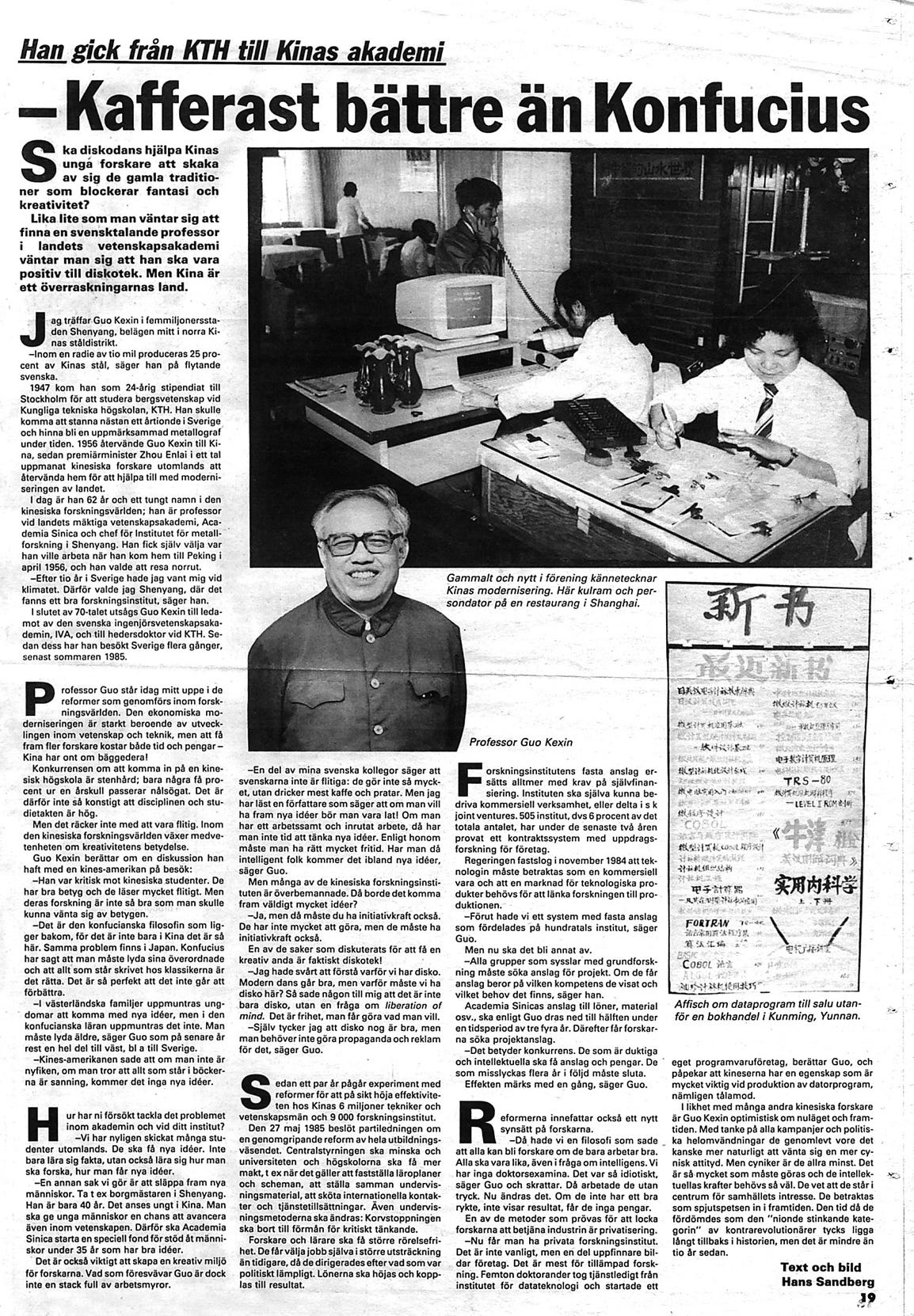

Could disco dancing help China's young scientists shake off old traditions that block their imagination and creativity? Just as you wouldn't expect to find a Swedish-speaking professor in the country's Academy of Sciences, you wouldn't expect him to be in favor of disco. But China is a country of surprises.

I meet Professor Guo Kexin in Shenyang, a city of five million in the heart of northern China's steel region.

“Twenty-five percent of China's steel is produced within a ten-mile radius,” he says in Swedish.

Guo Kexin was 24 in 1947 when he arrived in Stockholm on a scholarship to study mining engineering at the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH). He would stay in Sweden for almost a decade, becoming a renowned metallographer in the process. In 1956, he returned to China after Premier Zhou Enlai made a speech urging Chinese scientists abroad to come home to help modernize the country. Today, at 62, he is a big name in the Chinese scientific community; a member of the academy of sciences, Academia Sinica, and director of the Institute of Metal Research in Shenyang.

He says that was given a choice of where to work when he returned to Beijing in April 1956.

"After ten years in Sweden, I had gotten used to the climate. That's why I chose Shenyang, which had a good research institute."

In the late 1970s, he was appointed a member of the Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA) and an honorary doctor at the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH). Since then, he has visited Sweden several times, most recently in the summer of 1985.

Professor Guo Kexin is at the heart of the reforms being implemented in the world of research. The economic modernization is heavily dependent on science and technology but producing more researchers requires both time and money – and China is short on both!

The competition to get into Chinese universities is fierce; only a few percent of each cohort are accepted. It’s not surprising that both discipline and study tempo are high, but being diligent is not enough. In the Chinese research community, there is a growing awareness of the importance of creativity.

Guo Kexin recounts a discussion he had with a visiting Chinese American:

“He was critical of Chinese students, saying that they have good grades and read diligently, but their research is not as good as you would expect from the grades.”

"Behind this lies the Confucian philosophy. It's not only in China that it's like this, because we have the same problem in Japan. Confucius said that you must obey your superiors and that everything written by the classics is correct. It is so perfect that it cannot be improved.”

"In Western families, young people are encouraged to come up with new ideas, but this is not encouraged by the Confucian doctrine. You must obey your elders," says Guo Kexin, who in recent years has traveled a lot to the West, including to Sweden.

"The Chinese American said that if you are not curious, if you believe that everything in the books is true, there will be no new ideas.”

How have you tried to tackle this problem in academia and at your institute?

“We have recently sent many students abroad. They will get new ideas, not only learning facts, but also learning how to do research, how to get new ideas,” he says.

“Another thing we do is to let give new people a chance. Take the mayor of Shenyang as an example. He is only 40 years old, which is considered young in China. You should give young people a chance to advance in science as well. That's why Academia Sinica is planning to start a special fund to support people under 35 who have good ideas.”

It is also important to create a creative environment for researchers. Guo Kexin is however not thinking of researchers busy as bees.

"Some of my Swedish colleagues say that Swedes are not diligent: they don't do much, they mostly drink coffee and talk. But I've read an author who says that if you want new ideas, you should be lazy! If you’re always busy and your job strictly regulated, you don't have time to come up with new ideas. To him, you need a considerable amount of free time. Sometimes new ideas will come, if you have intelligent people," he says.

Should we expect a lot of new ideas since many Chinese research institutes are overstaffed?

“Yes, they don't have a lot to do, but you also need the power to take initiative.”

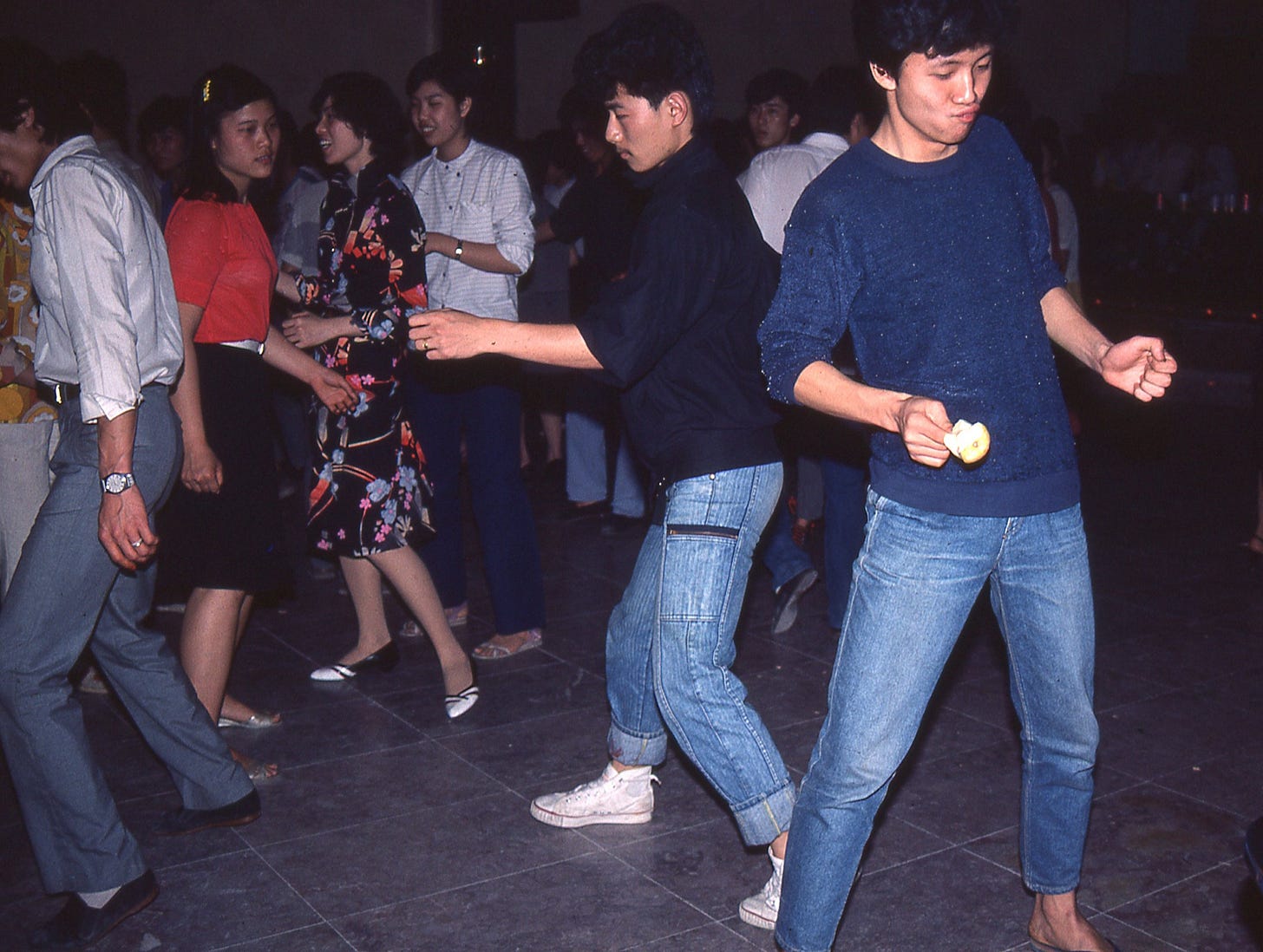

One of the things being discussed in China to stimulate the creative spirit is discos!

“I had a hard time understanding why we have discotheques. Modern dance is fine, but why do we need to have discos here? Then someone told me that it's not just discos, but a matter of liberating the mind. It's the freedom to do what you want.”

“Discotheques are probably good in my mind, but you don't need to make propaganda and advertising for it," says Guo Kexin.

Reforms have been under way for a couple of years now, aiming to improve the efficiency of China's six million technicians and scientists and 9,000 research institutes.

On May 27, 1985, the Communist Party leadership decided on a sweeping reform of the entire education system. Central control would be reduced, and universities and colleges should be given more power, for example in setting curricula and schedules, compiling teaching materials, managing international contacts and appointments. Teaching methods will also change; rote memorization and passive learning will be eliminated in favor of critical thinking. Researchers and teachers will also have more freedom of movement. They will be allowed to choose their own jobs to a greater extent than before when they were directed by what was politically expedient. Salaries will be raised and linked to results.

Fixed grants for research institutes are increasingly being replaced by requirements that they find ways of financing their work independently. Over the past two years, 505 institutes, or 6 percent of the total, have tested contract research for corporate clients.

In November 1984, China’s government decided that technology must be seen as a commercial product and that there is a need for a market for technology products to link research to production.

“In the past, we had a system of fixed grants distributed among hundreds of institutes,” says Guo Kexin.

But now things will be different.

"All groups involved in basic research must apply for funding for projects. Whether they get a grant depends on the skills they have demonstrated and the need," he says.

He says that Academia Sinica's funding of salaries, materials, etc. will be cut in half over a period of three to four years. After that, researchers will have to apply for project grants.

"This means competition. Those who are good and smart will get grants and money. Those who fail several years in a row will have to stop. The effect is immediately noticeable," he says.

The reforms also include a new approach to researchers.

“Our philosophy used to be that everybody can become a researcher if they work hard. Everyone should be equal, even when it comes to intelligence. We don't have doctoral degrees. It was so stupid," he says, laughing. “They worked without any pressure, but this is changing. If they don't have a good reputation and don't show results, they don't get funded.”

Privatization is also tested as a method for enticing researchers to serve industry.

“You are now allowed to have private research institutes. It's not common, but some inventors are starting companies. It's mostly for applied research. Fifteen PhD students took a leave of absence from the Institute of Computer Technology, and started their own software company," he says, pointing out that the Chinese have a characteristic that is very important in the production of computer programs: patience.

Like many other Chinese researchers, Guo Kexin is optimistic about the present and the future. Given all the campaigns and policy reversals they have experienced, one would have expected a more cynical attitude, but they are not the least cynical. There is so much that need to be done, and the intellectuals’ capabilities are badly needed. They know that they are at the center of society's expectations. They are seen as the spearhead of the future. The time when they were condemned as the ‘ninth stinking category’ of counterrevolutionaries seems like a long time ago, but it is less than ten years ago.